Bypassing CDN WAF’s with Alternate Domain Routing

Bypassing CDN WAF’s with Alternate Domain Routing

Update: Check out the updated version of this post on the APNIC blog. It addresses some questions I received and is much clearer thanks to Kubilay’s constructive feedback.

Related Tools: cdn-proxy

Introduction

Content Distribution Networks (CDNs), such as CloudFront and CloudFlare, are often used to improve the performance and security of public-facing websites. Standard features of CDNs like these include IP firewalling, client authentication, and WAF filtering. These controls present obstacles for an attacker when trying to exploit web application vulnerabilities that may exist in the underlying application.

Restricting the ability for attackers to bypass the CDN and access the origin server is critical to the effective implementation of the security controls CDNs offer. Despite this, preventing unauthorized access to the origin is a detail often missed during implementation of the infrastructure.

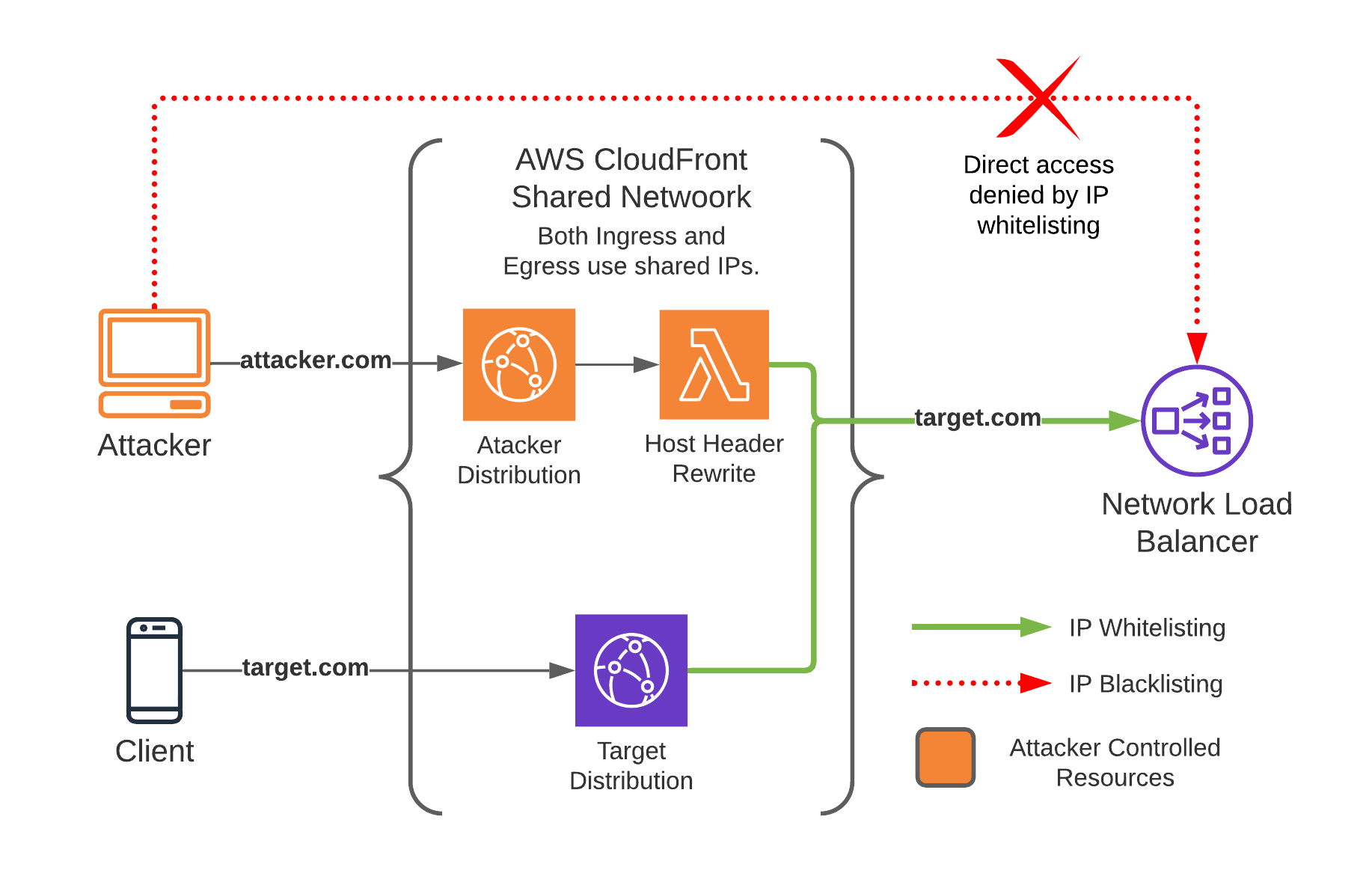

Other blog posts have covered the security risks of directly accessible origin servers at length. I won’t be covering this specific misconfiguration in this post. Instead, I’ll focus on a similar attack which is often the result of attempting to fix this vulnerability by IP allow listing the CDN’s IP range. This IP range is shared across all customers, so IP allow listing is insufficient to restrict access to the origin to traffic traversing the intended CDN distribution.

To demonstrate this issue, I created two tools: cdn-proxy and cdn-scanner.

- The cdn-proxy tool can be used to automate the deployment of the required infrastructure for this attack.

- The cdn-scanner tool uses the infrastructure set up by the cdn-proxy tool to enumerate many origin IPs and determine which are vulnerable to this attack.

In-depth information on these tools can be found on the cdn-proxy GitHub repo.

Inspiration, Other Work, and Changes

Aidan Steele originally tweeted about the idea behind this attack back in 2020 here and is the reason why I was aware of the issue when I started working on this project (Aidan: thank you! and sorry for forgetting about this).

I also want to thank my co-workers at Rhino Security Labs for taking the time to provide early feedback and review of this work (i of course still claim responsibility for any errors or not so best writing tho).

Interestingly some work that was similar in implementation was done by Mingkui Wei for Usenix and the Tor Project, this approaches the same idea from a privacy perspective rather than security. Personally, I find it interesting that the same concept can have very different results depending on how you think about it.

Around the time I published this, I came across Adam Pritchard’s thorough post on the XFF (linked below) and reached out to him about this issue. You can find his notes on how this affects the X-Forwarded-For header on CloudFlare here. In short, CloudFlare treats this as a protected header, so the IP spoofing attacks described in this post, in general, will not work on CloudFlare if you are using that header (please do not rely on this though, as Adam said in his post “Always do strong verification of your CDN!”).

Lastly, but very important if you use CloudFlare, Dhruv Ahuja pointed out on the Cloud Security Slack channel that CloudFlare has three types of Authenticated Origin pulls, and not all of them will protect against this attack. Check out the remediation section again if you read this before and use this mitigation.

How The Attack Works

This attack is relatively straightforward, given you understand the Shared CDNs operate above layer 4 of the OSI model. This means they terminate TCP connections on their network and make a separate TCP connection to the origin. This in turn, means that all connections through a CDN will be made from the client to an IP address the CDN network owns. Additionally, when a connection needs to be made to the origin (your backend server), it is also made with a source IP address that the CDN network owns.

- Shared CDNs such as CloudFlare and CloudFront use a shared IP range for all requests to the origin.

- Security features implemented by the CDN will only be applied to a request if it passes through the intended distribution (i.e, virtual host/configuration).

- Arbitrary origins (service backends) can be added to any distribution regardless of who owns it.

These conditions make it possible to bypass restrictions implemented in the real distribution by routing it through one in your control. This unfiltered request can bypass any IP restrictions at the origin because it originates from the same IP range as legitimate requests.

What Does This Enable?

This attack allows for bypassing security features that the CDN implements. This can be a Web Application Firewall (WAF), IP restrictions, rate limiting, and authentication. With security protections disabled in our custom deployment, requests that would typically get blocked in the original distribution get passed through to the backend without restrictions.

Scanning for origins that do not filter requests from the CDN is possible using the cdn-scanner tool, which compares responses from origins when queried directly to proxied through the CDN. When run against CloudFlare, the scanner will update the origin before every proxied request. This is highly parallel but can take some time waiting for the configuration to update before sending the proxied request. This delay can be sidestepped in CloudFront by taking advantage of Lambda@Edge to dynamically set the origin per request as it passes through the CDN, allowing requests to be proxied as fast as the cdn-scanner client can send them.

Additionally, in the case of CloudFront, when the X-Forwarded-For header is relied on by the backend application, the attacker will be able to spoof their IP address arbitrarily. I’ll briefly outline what X-Forwarded-For is and how it works to understand why this is applicable in most cases.

What Does This Enable? – X-Forwarded-For IP Spoofing

For an overview on what X-Forwarded-For, Adam’s blog post covers it comprehensively. I recommend reading that if you are not familiar with X-Forwarded-For or are interested in all the ways, it can go wrong.

This “Alternate Domain Routing” attack introduces an additional way for an attacker to manipulate the header when the request is passed to the origin. This attack will be possible in most cases where the CDN can be configured to add, modify, or passthrough the X-Forwarded-For (or similar) header(s) to the origin.

This attack is demonstrated in the CloudFront support of the cdn-proxy and cdn-scanner tools through per-request configuration headers. When the request is sent through our custom distribution, it retains the X-Forwarded-For header sent by the client. As long as the origin can not tell the difference between requests between the custom and real distributions and relies on X-Forwarded-For to determine the client’s IP, the application will see our spoofed IP.

Vulnerable Conditions

All of the following conditions must be met for this attack to work:

- The attacker knows the origin IP of the web application.

- Note: The cdn-scanner tool can be used to enumerate origins only accessible through the CDN.

- Access to the web app is allowed from the CDN’s shared IP range.

For this post, we’ll assume CloudFront is being used, however, this attack may apply to other CDNs as well. Both the cdn-proxy and cdn-scanner tools, detailed later on in this post, support both CloudFormation and CloudFront currently.

PoC Video: Bypassing CDN WAFs with alternate domain routing

In the video below I show the process of going from an entirely locked down website to gaining access through a distribution we control. When using this new distribution, any IP restrictions and WAF protections in place on the original web site will be disabled.

Conclusion: Attack Mitigation Options

While I focused on CloudFront and AWS WAF in this example, this misconfiguration can arise on any CDN that uses a shared pool of IPs for origin requests.

In the case of AWS CloudFront, the documentation provides recommendations for restricting access to the origin when using an S3 bucket or ALB. In other cases, you can use an approach similar to what is recommended for ALBs; enforcing a requirement that a specific header is present on requests in the backend web server configuration or application code.

In the case of CloudFlare, the documentation recommends using either CloudFlare Tunnels or Authenticated Origin Pulls. Although an approach similar to AWS’s ALB recommendations could be used as well; setting a header as requests pass through the CDN which is verified at the origin.

Update On CloudFlare Authenticated Origin Pulls

CloudFlare Authenticated Origin Pulls can operate in a few different ways and not all of them will protect against this attack. I haven’t thoroughly dug into this yet and don’t want to get things slightly wrong, so I’m going to quote Dhruv Ahuja here.

CF for example has “authenticated origin pulls” (as you have pointed out.) But within it there are three levels:

- Zone-Level — CloudFlare certificate

- Zone-Level — Customer certificates

- Per-Hostname — Customer certificates

Only the last two, with customer certificates, prevent the sort of routing/shadowing that you’ve discussed. All three are Mutual TLS so will require change at the origin, but only the customer certificate options set the authn uniquely enough to prevent those who don’t have the key to a specific client cert expected on the origin from connecting at all.

But to summarize, the first option (Zone-Level - CloudFlare certificate) is used across all CloudFlare customers. It does not offer any protection from this attack because you are only authenticating that the request came from CloudFlare, not your specific distribution in CloudFlare. The cdn-scanner tool currently does not support this configuration, so it may appear to be protected. However, this is misleading as the attacker only needs to turn on the same “Zone-Level - CloudFlare certificate” setting in the fake distribution.